Goals and Communication: Better Together

Dan and I have faced a complex set of challenges with regards to goals and communication within our relationship. Dan continues to adapt and recover after sustaining a traumatic brain injury. I am autistic. While I sometimes joke that we have one whole brain between us, it is true that we mutually benefit from each others’ unique perspective, problem-solving skills, and strengths.

For different reasons, we both experience difficulties with executive function, working memory, and communication. Some of the strategies I have created to help myself navigate daily life have also proved helpful for Dan. The habits, lists, and routines that conserve my mental energy also facilitate a predictable and secure environment. Dan, due to his condition, requires that I be flexible.

As a balanced and complementary pair, we both grow and thrive.

Dan and I each work independently with our own psychotherapists, and we participate in each other’s therapy as well. After receiving positive feedback from both therapists, I would like to share with you the creative solutions I developed for Dan and myself to use. One is to aid with achieving long-term goals. The others are to improve cognitive empathy and communication skills.

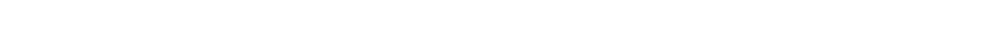

The Goal Puzzle

The first idea came in response to the process of Dan gradually regaining his independence and rebuilding his life. Starting over from almost nothing would be overwhelming for anyone. It is unimaginably complicated and emotionally taxing after a debilitating injury. While medical science made Dan’s physical recovery possible, returning to “normal” life is a gradual, often frustrating process.

While Dan was hospitalized, his family and friends — unsure if he would live — moved him out of his apartment. His belongings were then distributed amongst those same family and friends for storage. Dan woke from a medically-induced coma to discover that his previous home was gone. Any sense of constancy or stability was gone. His ability to care and provide for himself was gone.

Dan had to cope with nearly losing his life in more ways than one.

My heart ached for Dan after watching him psychologically struggle with the enormity of what lay ahead. One night, after we had retrieved his beloved record collection, I downloaded a blank puzzle template. I labelled the “pieces” of Dan’s life to be reassembled. I left a few blank pieces for him to fill in. One of those blanks eventually became “Married.” There are short- and long-term goals.

The puzzle concept helps to break down and visualize the seemingly immense goal of “rebuild Dan’s life” into incremental, more managable steps. After having Dan colour in the “accomplished” pieces, I hung the puzzle on the refrigerator as a daily reminder of the progress he has made. Pieces continue to be coloured in, partially or completely, as Dan and I achieve our individual and joint goals.

This can be a powerful tool to improve motivation and resilience.

Think about it: What would you put on your puzzle?

Autism and Cognitive Empathy

The second idea is more specific to our circumstances, but it can be easily adapted to accommodate other situations. In order to help Dan and I understand our communication styles and needs, I purchased a pair of books related to both of our conditions. The books that I selected were written specifically to cultivate understanding in people who do not live with the conditions themselves.

For myself, I chose — and I highly recommend — Connecting With the Autism Spectrum by Casey “Remrov” Vernor. First, I read the book myself. Using a pencil and highlighter, I made notations where I felt the text was most applicable to me, and elaborated where I felt it was needed or warranted. After completing that process, I gave the book to Dan. By reading it, he gained valuable insight.

Learning about autistic communication and sensory sensitivities helps Dan, for example, to not take it personally when I become confused or overstimulated by something in our environment. As a result, such occurrences can be prevented or remedied easily, without escalating into anxiety, conflict, or hurt feelings.

We are learning how to listen to, and speak with, each other in ways that minimize miscommunication and misunderstandings. Dan understands that my communication tends to be blunt. The words I choose do not always accurately reflect what I am attempting to say. Statements made to me should be clear, consistent, and direct. My innate mind-reading skills are incredibly poor.

I now utilize self-advocacy and self-directed questioning to circumvent my limitations in social interactions with neurotypical people. I will elaborate on my compensatory strategies in future posts. The projection of neurotypical thought processes onto neurodivergent individuals is one of many ways these mixed-interactions go wrong. Education and cognitive empathy are essential.

When we use different languages, translation is necessary.

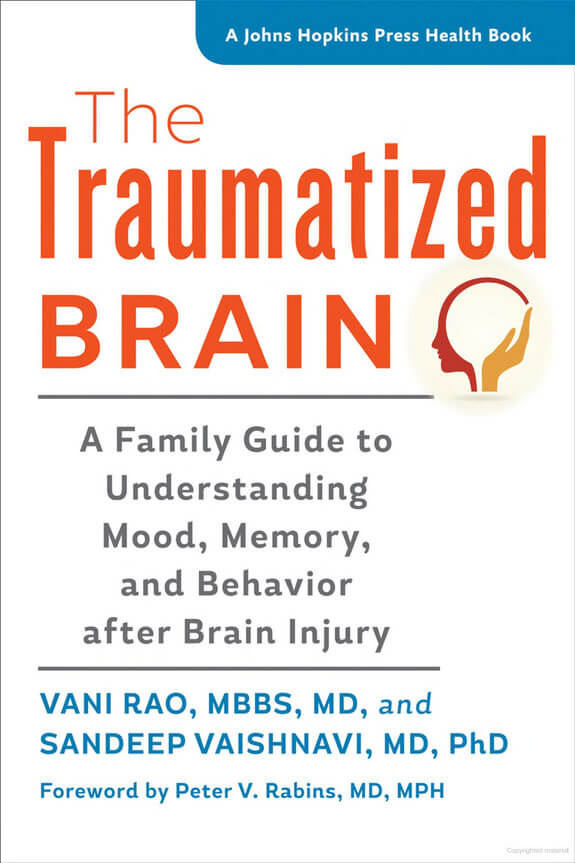

Traumatic Brain Injury

For Dan, I chose The Traumatized Brain: A Family Guide to Understanding Mood, Memory, and Behavior after Brain Injury by Vani Rao and Sandeep Vaishnavi. I asked him to read and notate the book for me, like I had done with mine.

Learning about traumatic brain injury, and how it affects Dan, helps me remain patient and supportive while he continues to heal. Forgetfulness is not indicative of lack of caring or interest, but a result of injury and trauma. Fatigue is not a character flaw, but a result of living with disability. We all benefit most from support that makes us feel empowered, not dependent and indebted.

Dan and I hold each other accountable with compassion and tenderness.

Two additional books I found valuable, especially if you had limited or no experiences of healthy relationships while growing up: Mindful Relationship Habits: 25 Practices for Couples to Enhance Intimacy, Nurture Closeness, and Grow a Deeper Connection by Barrie Davenport and S. J. Scott, and The Seven Principles for Making Marriage Work by John M. Gottman and Nan Silver.

Even if you are chronically single, these books can teach you to recognize the healthy and toxic traits in nearly any kind of relationship. That knowledge makes you a less likely target for abusive, dysfunctional, and exploitative relationships. If you are objectively self-aware enough, these books also provide a solid guideline for evaluating and nurturing your own behaviours.

I am a big fan of The Gottman Institute, generally.

Additional Communication Ideas

As part of ongoing efforts, I purchased a lined journal for Dan and myself to share. In the morning and evening, we each write a few lines in the journal. The short entries consist of whatever is on our mind at the time: what we are grateful for, what we are doing or plan to do, progress made toward our goals, things we might be struggling to communicate verbally, and so on. There are no rules.

Write when — and what — comes naturally. It should not be stressful.

Using multiple ink colours makes the daily entries easier to follow.

Because we both contribute, reading and writing in the journal gives us a window into each other’s inner world on a day-to-day basis. Reviewing our older entries serves as a source of encouragement, mindfulness, and reassurance.

Over time, the journal serves as a reminder of what brought us together.

For this idea to be effective, however, it requires honest self-reflection and the willingness to be vulnerable. If these are areas that you struggle with, try writing privately for yourself. When you are ready to step outside of your comfort zone, share your daily journaling with your psychotherapist or a trusted friend.

Shared goals, successful teamwork, and meaningful relationships are among the richest experiences life has to offer. For those with disabilities and/or impairments they are, in my opinion, goals worth doing the hard work. Our world desperately needs authenticity, human connection, and the healing that comes with it.

Better communication and collaborative goals are an excellent place to begin.

I hope that what I have shared today helps you in your journey.